When I was studying composition at the Qld Conservatorium of Music in the late 1980s, all I ever heard about was “Brian Eno this,” and “Brian Eno that.” All of the students (and teachers for that matter) were so enamoured of Eno and his work (especially the ambient material) since it was “clever” (good) but didn’t sound anything like the fingernails down a blackboard of Ligeti or whoever-else was considered important at the time (even better). For the record, I love Ligeti’s work (you may have heard some in Kubrick’s The Shining)…fingernails and all.

With Eno’s music you got to have your musical cake and eat it too. You got the procedural kudos of John Cage et al combined with the sensuality of a Debussy. Eno could even make Pachabel’s Canon sound good (that is, after putting it through a procedural wringer!).

Gaining insight into Eno’s work and ideas became a lot easier with the release of Eric Tamm’s very fine book Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Colour of Sound (1989) (remember, this was before the internet). Perhaps, the most striking revelations contained therein related to Eno’s down-to-earth character and his “somewhat superficial knowledge of the classical tradition and his disdain for its institutional infrastructure” (p. 20). Kudos!

Eno has remained productive in the years since and is (arguably) even more influential today. No doubt, he is also a lot wealthier thanks to his work with U2, and remains at the vanguard of popular music creative practice thanks to his embracing generative music and open source programming platforms (together with Peter Chilvers).

If you haven’t already read Tamm’s book, you might not be aware that Eno has made a living all this time by running away from a day job. That isn’t to say he’s not a hard worker. As a case in point, his slow and meticulous gradus ad parnassum approach to building up soundscapes was very much at odds with collaborator David Bowie’s first-take-is-the-best-take approach (see the hilarious video below). He is also capable of capriciousness: For example, if his infamous Oblique Strategies cards (developed together with painter Peter Schimdt) tell Eno to erase everything and start all over again, he’ll do it.

Eno: A Practitioner of Play

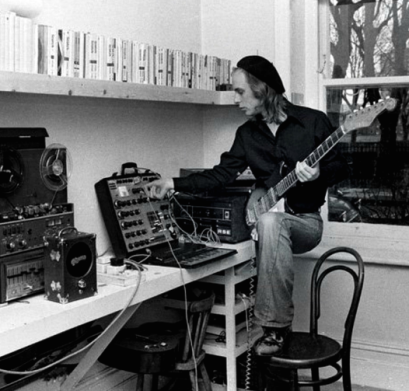

What I want to get across is that you’d be in error to put Eno on a pedestal. Anyone, can do it! That is, if you have the guts to go against all usual, well-meaning ‘advice’ from family, friends, loved ones and vocational guidance officers to get your life together. Do you have the wherewithal to devote 8 hours a day (or more) to play.

Instead of clocking on at the office, crunching numbers or pressuring pensioners into life insurance they don’t need, can you see yourself devoting that same amount of time to fiddling around with your DAW, Max/MSP, Pure Data or whatever musical means you prefer: juggling ideas, procedures, and sounds that – more often than not – will result in nought but creative dead ends? Probably not, given the low social status and financial instability that are for contemporary artists and musicians constant reminders of a comfortable life that might have been.

You’ll also need a refined and discerning sense of aesthetic appreciation. This is where Eno and John Cage’s procedural approaches to creativity diverge. Cage was happy to live with the results of his chance music, accepting it on its own terms, whatever the hell it sounded like (anyone for another 8 bars of ‘Fingernails down a Blackboard?’). Eno, ever the aesthete, instead spends a great deal of time reflecting upon the artefacts of his play before releasing them to public scrutiny. So much so that Tamm’s considers listening to be Eno’s “primary compositional activity” (p.49).

If you’d like to read more about Eno and his playful approach to creative practice check out my forthcoming book Popular Music, Power & Play: Reframing Creative Practice.

References:

Heiser, M. (2021). Popular Music, Power and Play: Reframing Creative Practice. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.